Chart One: Share prices of antibiotic pharma companies have plumeted.

The market mechanism is a remarkable process. Buyers and sellers exchange money in an open system that produces prices and production levels to equate supply and demand. (Also known as Keynes’ invisible hand, the market mechanism is an alternative to central planning.) Chinese leaders added the market mechanism to its communist political system, and economic growth skyrocketed.

In theory, the market mechanism leads to an ideal allocation of goods, services and workers’ efforts for society. In practice, ideal output misses the mark when prices fail to reflect societal benefits and costs, consumers are not well-informed, or monopolistic-like power exists.

One area where the market mechanism often fails is healthcare. A healthy population benefits everyone, from employers in need of a productive workforce to the government (and taxpayers) who cover the costs of the social safety net to each of us as individuals and our families.

Asking individuals to cover all the cost of their healthcare would lead to an underinvestment in health and society as a whole would suffer. The chances of my getting the flu are much higher if I live in a city where few people get a flu shot. Flu shots are often free for this very reason. (The same reasoning supports free public education through high school: we all benefit from having a more-educated populace.)

The situation gets even trickier because it’s impossible for us to gain the knowledge we need to be capable buyers of healthcare. On Amazon, we can see price and product comparisons and read user reviews before making a $20 investment. In healthcare, where costs are astronomically higher, we are either kept ignorant of the full costs and potential outcomes from different procedures or medications, or we have to rely on information from healthcare professionals who are largely paid today to “perform procedures.” That means we individuals will rarely if ever have the information we need to make rational purchasing decisions. This exception to the assumptions underlying the perfect market model can lead to an overuse of healthcare, as we see in end-of-life heroics with no return on the quality of life. Or, too much spinal surgery for back pain.

Let’s dive deeper into one area of market failure – antibiotics. We face a crisis with the rise of drug-resistant superbugs. For decades we overused antibiotics (in our farms and by prescription) because the price never reflected the societal costs of an increase in drug-resistant bugs. Today, these bugs kill 25,000 people a year in the US and make another 2.8M people ill according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotics were also overused because people were unaware of the societal costs (a situation that has thankfully changed, leading to less use of antibiotics).

According to market mechanisms, producers should jump to the market opportunity of new antibiotics. And many have—but they are failing miserably, as reported by the Wall Street Journal. (See Chart One.) It turns out that the price of creating a new antibiotic exceeds the return to the pharmaceutical company. One factor is that antibiotics are intended for short-term use, unlike the blockbuster drugs that are used regularly. Also, hospitals, which treat superbug infections, are not reimbursed the market price of these new drugs because the payment system bundles clinical care and drug costs in one payment. That creates an incentive to use cheaper, older drugs, even if they are far less effective. If the market mechanism were fully in effect, the price of the new and improved drugs would plummet because of these factors. But investment in R&D on new antibiotics would stop, a terrible outcome for our society.

What is a nation to do?

Welcome to the entangled world of healthcare policy. We can solve the specific problem of antibiotic cost and usage in any number of ways, from changing how we incentivize pharmaceutical firms, to changing reimbursement for infections, to having the US government’s National Institutes of Health develop and supply antibiotics.

Now let’s broaden the lens. Multiply this one situation by the hundreds of others affecting how healthcare markets perform in the US. Consider just a few factors:

- an increasingly obese and sedentary nation with limited incentive to change

- technology that can, very expensively, extend life at the start or the end and incentives to use it

- employers providing healthcare benefits, making our labor more expensive in global markets

- the extraordinary expense of medical education, leading to an excess of higher-paid specialists and too few primary care doctors

- limited competition as systems, drug companies, and insurers consolidate their industries

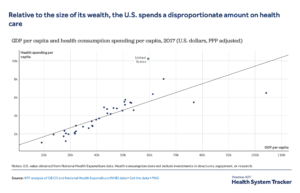

Chart Two: US pays a premium for its healthcare costs.

Deciding the future of healthcare policy will not be simple, even if we could ignore the politics. Step One will be to decide on the aims of the system. Historically, our healthcare systems’ purpose was, in effect, to treat illness effectively (not necessarily efficiently) and in the process generate income for providers, insurers, and healthcare product and service companies. It has produced very high costs relative to other nations (See Chart Two), and frighteningly high levels of avoidable harm and unnecessary care. It’s also produced enormous income for all those organizations listed above, which is where the pushback comes on any reform effort.

Our aim going forward should be to keep people healthy, efficiently, while treating unavoidable disease effectively and efficiently. Keep this in mind as election-year politics cloud healthcare reform debates. We must make decisions about how we pay, how we regulate, who is at risk, and the structure of our risk pools (universal or segmented, as they are now) with this aim in sight.

If we succeed, more Americans will have access to better care at more affordable prices. To do that, we’d have to lessen or contain spending on healthcare, which means winners and losers in the marketplace. I’ll write about this topic in Part Two. But our nation will for sure be a loser if we do not reform how the system works today.

Leave a Reply